Women's History Month HERstories by Lisa Tanner

As Women’s History Month comes to a close, we salute all women who continue to challenge and inspire us all.

Lisa Tanner, ICAN’s Director of Adult Services, has compiled stories about the not-so famous, or unsung heroines, that changed the course of history. While these are by far not the only stories (see reading list below) of women paving the way for all the daughters and granddaughters born after them, but they hopefully enlighten and motivate us to do our small part to make the world a better place for all.

The following are … HERstories:

The Empowerment of Women in the early 1900’s, during the Great Depression

Ellen Sullivan Woodward and the Pack Horse Library Project

This story is about not just one woman, but how one woman stood up to traditional beliefs and made the lives of other women of the time better. In 1925,a Mississippi-born and raised woman, Ellen Sullivan Woodward (b.1887-d.1971), was elected to serve in the Mississippi State Legislature after her husband, who held the position, died an untimely death at age 37. She became only the second woman to serve as that state’s representative.

Although Ellen did not have any formal education after the age of 15 because her father did not want her to attend college, she focused her policies around libraries, education and charities. Part of her motivation to run for the position was to support her young son, but soon found that the salary was not sufficient to support the two of them. Ellen did not run for re-election, but instead began work in local and state programs centered around civic development and women’s programs.

After several promotions, Ellen became the Director of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, a division started through pressure from Eleanor Roosevelt (a pioneer in her own right) to support unemployed women. Parts of her work included creating jobs for women through the Civil Works Administration, created in 1933, under President Roosevelt’s New Deal reforms. Starting these jobs would be hampered because public opinion didn’t often see women as the head of the household and had beliefs about what types of jobs would be appropriate for women to hold. Some direct relief was given out, but Woodward preferred training women for jobs instead of giving out direct monetary relief.

Through creative thinking and bold determination, that program then became the Works Progress Administration, employing over 500,000 women in jobs from 1933-1938. One newly created job project was the Pack Horse Library Project. These positions allowed women in severely poverty-stricken eastern Kentucky to deliver books in rural areas along the Appalachian Trail. These women were able to earn a salary and help support their families. In doing so, they encountered daily, life-threatening barriers – bad weather, danger from animals and human predators along their routes, in addition to the long hours on horse or mule back through rugged terrain traveling from the in-town libraries to the hollows of Kentucky, where the Great Depression was especially brutal, to those living in isolation without electricity and using creek beds as “roads”, and the only jobs were in the mines where life-expectancy was 35.

Those brave women provided all forms of reading materials (and many times first aid, food and an outside person to talk to) to those that could read and read to those who could not. In turn, those “patrons”and rural schools receiving the book deliveries saw literacy as a way out of their stark existence and provided hope, especially to women who were intrigued and interested in the possibility that they could work too.

Thank you Ellen Woodward and the “book women” of the Pack Horse Library Project. A story about ONE woman working out of necessity and with compassion and a vision to help other women to change the course of their lives and history!

The Pioneer of Social Work and Social Change

Jane Addams

In Illinois in 1860, Jane Addams, the eighth of nine children, was born into a well-connected, prosperous family, counting Abraham Lincoln as her father’s good friend. Unfortunately, Jane suffered from a congenital spinal defect that would change the course of her life – and society would benefit.

By the time Jane was eight years old, she had endured the deaths of her mother and four of her siblings. Due to Jane’s physical affliction, she walked with limp, and she considered herself an “ugly” girl, who didn’t participate in much of the outdoor play with other children. From spending the days inside, she became a voracious reader, and was especially fond of Charles Dicken’s account of the poor people in society. Jane’s dream was to become a doctor to help poor, sick children.

After graduating college as valedictorian, Jane would not receive her bachelor’s degree until two years later, when the school became accredited as a College for Women. After college, Jane became plagued with poor health and instead of becoming a doctor, she spent much of the next years as a patient. Not to be deterred, Jane was eventually well enough to travel abroad in search of what her next career path might be.

On a London trip with her good friend Ellen Gates Starr, they decided to visit Toynbee Hall, a facility to help the poor. They became so inspired to bring that kind of facility to help the poor back home, that they leased and moved into an old mansion in an immigrant neighborhood of Chicago. Their sole purpose was to provide a center for a “higher civic and social life, maintain education and philanthropy, and to improve the conditions” in the industrial districts of Chicago.

In that first year of 1889, Jane and Ellen gave speeches about the needs of her neighborhood, raised money, convinced well-to-do young women to help, took care of children, nursed the sick and listened to the troubles of their neighbors.

By its second year, the mansion – now named “Hull House” – saw the development of kindergarten classes in the morning, clubs for older children in the afternoon, and night school for adults. The women added an art gallery, a second public kitchen, a coffee house, a gym and pool, a library, boarding club for girls, a book bindery, art and music studios, a drama group, employment bureau and labor museum – all while hosting over 2,000 people each week!

As Jane’s reputation grew in the community, she was asked and appointed to other positions in education leadership, becoming prominent on school boards and pioneering reform with child labor and juvenile justice inequities. In 1901, she founded the Juvenile Protection Agency, and established the first juvenile probation officers and juvenile court system.

Jane’s work in founding stricter labor laws for children and protection for women in the workplace, was fueled by not only her constant research and studies, but colleagues and friends. Hull House residents were social work students, local artists, and women interested in conducting investigations on every facet of society, including illnesses, drug use, truancy, housing, education, even sanitation; all in an effort to improve the lives of the immigrants and the poor in their area of Chicago. Jane frequently brought in world-renowned artists, musicians, and designers to hold lectures or teach classes where all in the neighborhood were welcome.

Jane soon wrote books and lectured on peace, being an opposer to the First World War. She was a supporter of the Hague and attended and spoke at the ceremony of the newly built Peace Palace there. In 1910, she was the first woman ever to receive an honorary degree from Yale University.

While Jane was a respected leader for women’s rights to vote, foreshadowing the suffrage movement, and speaker of peace worldwide, she was viciously attacked by the press and kicked out of the Daughters of the Revolution. Jane only increased her leadership in these groups and continued to write books on peace.

It has been said that Jane Addams was the most famous woman in America when she died in 1935, after another bout of illnesses and hospitalizations. A lot of what accomplished is work that we and this agency do every day.

Thank you Jane Addams for disrupting fixed ideas and stimulating diversity, interaction, action, and free thought-and for paving the way for future generations to have the right to do the same.

A Steadfast Leader and the “Godmother” of Civil Rights

Dorothy Height

Dorothy Height, born in 1912, in Richmond Virginia, became a true example of a life dedicated to service, especially for civil and women’s equality in the United States.

At the age of 5, Dorothy’s family moved to Rankin, Pennsylvania, where she attended a racially integrated school. Although Dorothy’s childhood was burdened with bouts of severe asthma (her parents were told she would not live more than 16 years), she excelled at school, and was an exceptional orator. In high school, Dorothy began her life-long quest for civil rights, volunteering on voting rights and advocating on anti-lynching campaigns.

She used her skills as an orator by entering the National Oratorical Contest, making it to the finals, the only black contestant, delivering a talk on the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments of the US Constitution-the Reconstruction Amendments – intended to extend constitutional protections to former slaves and their descendants. The jury, all white, awarded her first prize – a four-year college scholarship. Her heart set on attending Bernard College in New York City, she applied and was overjoyed when she received her acceptance letter. That joy soon faded in the summer of 1929 when shortly before her first semester was to begin, she was called to meet with the Dean, who promptly told her that she could not attend Bernard, at least not that year, because the college already had its quota of Black students - only two allowed per year. Upset, disappointed and too distraught to call home and tell her parents, she turned that event into an opportunity and took the subway to NYU and was accepted on the spot, earning a degree in education and continuing to earn a Master’s Degree in Psychology two years later. It seemed that Dorothy Height knew how to make things happen against the odds and obstacles in her path.

Upon graduation, Dorothy worked as a caseworker in the NYC Welfare Department before becoming the Assistant Executive Director of the Harlem YWCA. One of her first public acts was in the late 1930s when she called attention to the exploitation of black women as domestic day laborers. The women, who congregated on street corners in Brooklyn and the Bronx, locally known as “slave markets,” were picked up and hired and paid about 15 cents an hour by white suburban housewives who cruised by in their cars. Dorothy brought the issue to the City Council, the publicity from it and the embarrassment of the housewives drove the “slave markets” underground for a while, later re-emerging.

Undeterred, and over the course of the next few years, Dorothy became a steadfast leader for civil rights, in the beginnings of what was becoming a civil right movement in the US. Through a series of career advancements and public speaking, Dorothy was making tremendous strides and gaining national attention for her work at desegregating the Y’s facilities and speaking out on women’s and civil rights.

During this time, Dorothy had a life-changing experience when the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune, founder of the National Council of Negro Women, came to visit the Y. Being impressed with Dorothy and her dedication to the cause of the rights of black women, Mary struck up a friendship and soon became a good friend and mentor to Dorothy, who volunteered often and was elected president of the organization in 1957. Dorothy wrote later that she felt she “found her sisterhood” with the women of the Council.

Through her work with both the Y and the Council, she met key figures in the civil rights movement: Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, James Farmer, Roy Wilkins, A. Phillip Randolph and Whitney Young – the “Big Six” of the movement – and worked with them on several campaigns and initiatives. Dorothy organized the March on Washington and was with King when he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. A gifted and eloquent speaker, she was not invited to speak that day, later writing that her male counterparts were “happy to include women in the human family but there no question on who headed the household.” An eye-opening experience for her, Dorothy joined the fight for women’s rights in 1871, with Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Shirley Chisholm. Dorothy who never married or had children, focused her later projects on the African American Family, and in 1986 formed the first Black American Family Reunion, a celebration of values and traditions, which is still held annually.

These events are just some of the milestones in Dorothy Heights long life of service, using her opportunities as a platform as a way to not only call attention to, but to act, on behalf of racial justice, to make real advances toward that goal. Dorothy earned many awards in her life but those most notable are:

The Freedom from Want Award in 1993, awarded by President FDR

The Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded in 1994 by President Bill Clinton

The Congressional Gold Medal in 2004, awarded by George W. Bush

Three dozen Honorary Doctorate Degrees from institutions including Tuskegee, Harvard and Princeton; but there was one that resonated more than all the rest – an Honorary Degree designated from Bernard College.

Thank you Dorothy Height for making the world a better place through your life’s work and your kindness!

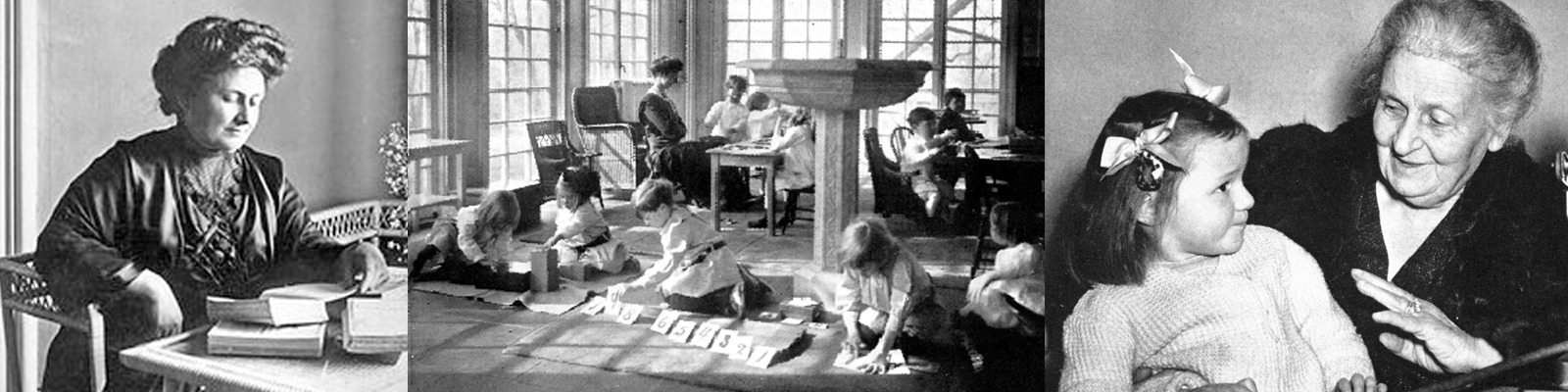

Maria Montessori

Trailblazer in Medicine, Education and Women’s and Children’s Rights

Born in 1870 and growing up in a time when women across the globe were beginning to challenge their lack of rights as compared to men, Maria Montessori would soon be quietly and unwittingly breaking gender norms.

As a young child, Maria was a talented, headstrong and self-confident student, traits that her well-educated and well-read mother encouraged. By age 13, Montessori, who was particularly gifted in math and science, enrolled in an all-boys technical school in hopes of becoming an engineer – then, an unheard of aspiration for a young woman. She only gained acceptance because of her high exam scores.

In the late 1800s, while other young women were readying themselves for marriage and motherhood, Maria was again pushing aside the expectations put on women of that time and planning her future as a doctor. Against her father’s and teacher’s wishes, she applied to medical school, only to be rejected. Maria, undeterred, studied harder and took additional courses, passing all exams in the sciences and even appealing to the Pope for special permission for admission- after two years of doing more than any other male for acceptance, was she was finally admitted into the University of Rome’s medical program – opening the door a bit wider for future women looking to become doctors.

In an almost exclusively male-dominated field, Maria would face hostility and harassment from her male classmates and professors because of her gender. At the end of her first year came the study of dissection. Because she was a woman and deemed inappropriate for a female to be amongst her male classmates in a room with a naked body – albeit a dead one – Maria had to perform the dissections alone, in the cold and dark morgue, after hours, where she found the smell of formaldehyde so offensive, she took up smoking to mask it. All of the humiliation and hard work paid off when Maria graduated medical school in 1896, becoming one of Italy’s first female doctors, and the only woman until that point to attend Rome’s prestigious Medical University.

Montessori earned many academic awards throughout medical school, especially for her work in pediatrics and psychiatry and she opened a private practice after graduation. She was also volunteering at a psychiatry clinic. As part of her work, she visited asylums in Rome where she observed children with disabilities, observations that were fundamental in her future educational practices. Through this experience and her own research through the last 200 years of educational and learning models, Maria opened a school for training teachers with learning disabilities.

It was at this school, along with other children in the community deemed “uneducable,” that Maria set up the model classroom with ideas drawn from the scientific world, her hours of observations from the asylums, and her ability to see how children developed at their own pace, with a natural curiosity and limitless propensity to explore and care for the environment around them in a sensory way. These practices and the model – “The Glass Classroom” – were showcased at the 1915 World’s Fair; showing onlookers a completely new approach to education that caught the attention of many international educators, scientists and inventors. Her methods were soon replicated in schools across the globe. Her schools were based on the philosophy that focused on independence where children were not “taught” but rather the teacher’s role was to set up the environment, and to observe so children could move freely about, exploring areas of their interest and developing their strengths, as well as overcoming obstacles and learning to self-correct without the need for adult intervention.

Maria’s work was groundbreaking and she was soon traveling the world giving lectures and trainings, not only on education, but on women’s and children’s rights and on peace, the latter earning her a Nobel Peace Prize nomination.

Montesorri continued her work passionately through the rest of her life, publishing a number of books, articles and pamphlets over her lifetime, translated (under her supervision) to over 50 languages work that continues today with over 5,000 schools in the U.S. alone. She was undeterred by bias, criticism, war and exile – a woman who dared to reimagine how we learn, and recognized the dignity and capacity of all human beings.

A very short list of well-known Montessori graduates:

Entrepreneurs: Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos,; Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Wikipedia Jimmy Wales, former CEO of Microsoft Bill Gates

Actors: George Clooney, John and Joan Cusak, Helen Hunt

Creative Entertainers: Magician David Blaine, Chef Julia Child

Musicians: Taylor Swift, Beyonce, Peace ambassador and cellist YoYo Ma

Authors: Maya Angelou, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Helen Keller

Other Notables: Mahatma Ghandi, Jackie Kennedy Onassis and Sean “Diddy” Combs